Dignity has gained increasing attention as a vital component of quality of life and quality of end-of-life care. This article reviews psychological, spiritual, existential, and physical issues facing patients at the end of life as well as practical considerations in providing therapy for this population. The authors reviewed several evidence-based treatments for enhancing end-of-life experience and mitigating suffering, including a primary focus on dignity therapy and an additional review of meaning-centered psychotherapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Each of these therapies has an emerging evidence base, but they have not been compared to each other in trials. Thus, the choice of psychotherapy for patients at the end of life will reflect patient characteristics, therapist orientation and expertise with various approaches, and feasibility within the care context. Future research is needed to directly compare the efficacy and feasibility of these interventions to determine optimal care delivery.

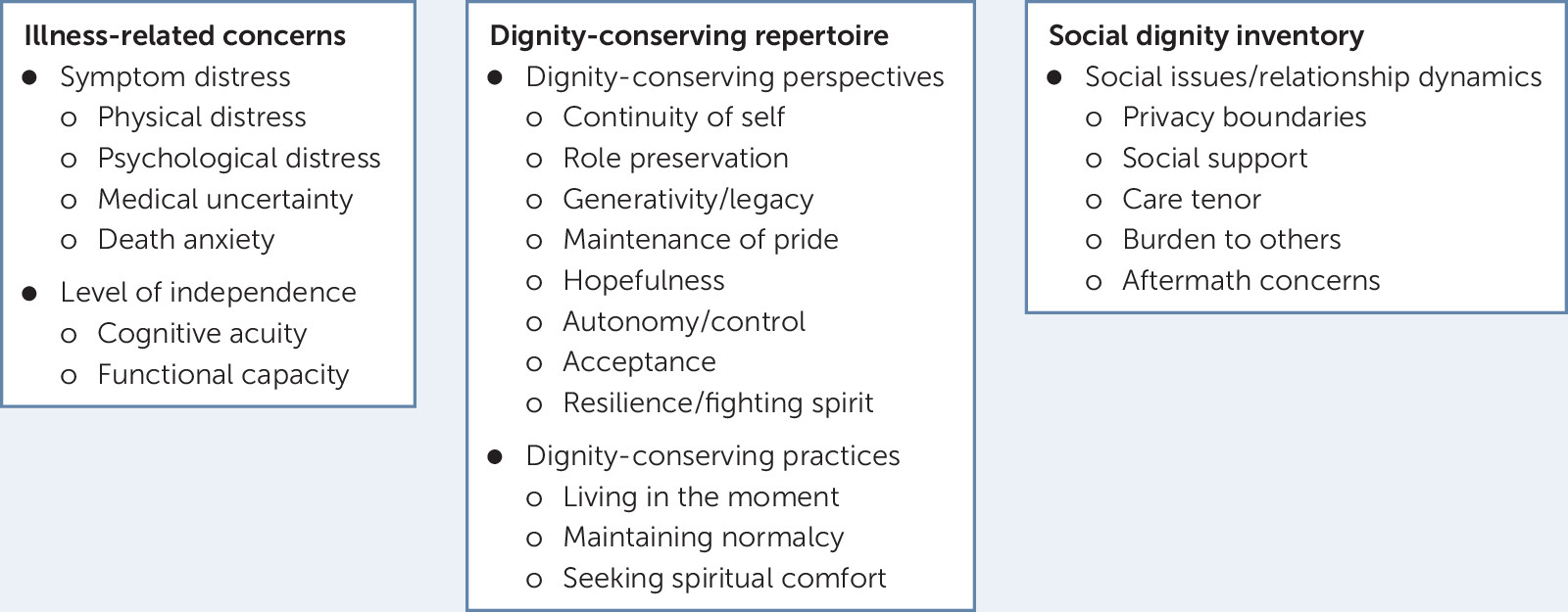

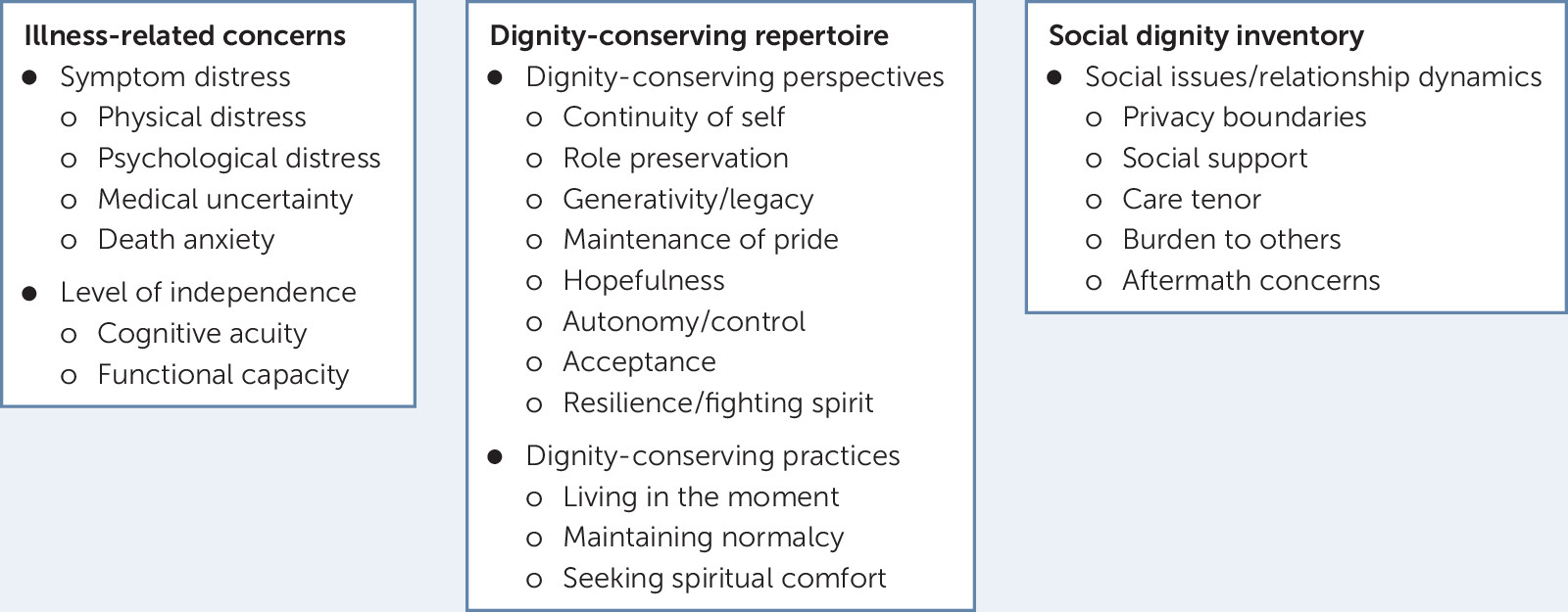

Because some elements of dignity are externally mediated, they can be influenced by the qualities, attitudes, and general disposition of the health care provider. Our research (22) has found that how patients perceive themselves to be seen by health care providers can profoundly influence their overall sense of dignity. Understanding of the psychological landscape of patients nearing end of life and the model of dignity for patients who are terminally ill provides an important context for applying psychotherapeutic interventions for this patient population.

Psychotherapy at the end of life includes the foundation of a strong therapeutic relationship that is based on trust, therapist empathy, presence, and unconditional positive regard for the patient and his or her emotional distress (23, 24). Therapists should have a good understanding of mental disorders and be able to differentiate between normal and abnormal coping and emotional expression at the end of life. They must also be mindful of a diminished and often unpredictable time frame for therapy and the need for flexibility in scheduling. Practical adaptations for therapists are reviewed in Table 1. These adaptations may include blocking out time to see patients as needed; allowing for rescheduling with little notice; seeing patients more often when they are well enough; decreasing the length of sessions as needed; and being open to including family members in treatment on the basis of patient preference, comfort, and need (25). Therapists must adjust to the patient’s goals and expectations of a good therapeutic outcome because these can fluctuate significantly depending on the patient’s medical status. Ongoing collaboration with the patient’s medical team while maintaining appropriate patient-therapist confidentiality is essential. At times, therapy may be focused more systemically on the patient and care team relationship in order to improve patient care. Consideration of how therapy may be terminated, possible lack of closure for the patient and therapist, and therapists’ management of their own beliefs and possible fears about death are important in providing effective care (25).

TABLE 1 . Practical adaptations to psychotherapy for patients receiving end-of-life care| Therapeutic issue | Practical adaptation |

|---|---|

| Unpredictable time frame for therapy | Flexibility in scheduling; blocked time to see patients as needed (on-call basis); more frequent sessions when patient is well; shorter session length |

| Goals of treatment | Adapt to fit patient’s medical status; include family members per patient preference; focus on patient and care team relationship to improve care if needed |

Psychologists, psychiatrists, and others engaging in psychotherapy in palliative care settings are well served by understanding the medical conditions and symptom challenges facing patients and how these symptoms interact with patients’ psychological distress (26). Care providers must also understand the developmental tasks associated with dying and the manifestations of emotional and existential distress. Therapists need to be aware of evidence-based psychotherapies for the range of mental health issues that may be encountered with patients who are at the end of life. A majority of psychotherapies have not been evaluated for use with populations receiving palliative care and may not be generalizable to this population (26). For instance, a Cochrane review of psychotherapy for the treatment of depression among patients with advanced cancer found that although psychotherapy (primarily supportive in nature) was useful for treating depressive states, there was insufficient research to support its effectiveness for patients with advanced cancer and clinically diagnosed depression, including major depressive disorder (27). Hence, below we offer a review of several evidence-based modalities developed specifically for patients with a terminal illness.

Dignity therapy is an established intervention for terminally ill populations, with demonstrated efficacy in enhancing end-of-life experience (28–31). This brief intervention targets sense of meaning, purpose, and dignity, and is based on the model of dignity for the terminally ill and related research (28–31). The therapy uses a framework involving open-ended questions delivered by a trained professional that elicit memories, hopes, wishes, life lessons, and the legacy the patient wishes to leave for loved ones (30) (Box 1).

Tell me a little about your life history, particularly the parts that you either remember most or think are the most important. When did you feel most alive?

Are there specific things that you would want your family to know about you, and are there particular things you would want them to remember?

What are the most important roles you have played in life (e.g., family roles, vocational roles, community service roles)? Why were they so important to you, and what do you think you accomplished in those roles?

What are your most important accomplishments, and what do you feel most proud of?Are there particular things that you feel still need to be said to your loved ones, or things that you would want to take the time to say once again?

What are your hopes and dreams for your loved ones?What have you learned about life that you would want to pass along to others? What advice or words of guidance would you wish to pass along to your [son, daughter, husband, wife, parents, others]?

Are there words or perhaps even instructions you would like to offer your family to help prepare them for the future?

In creating this permanent record, are there other things that you would like included? a Adapted from Chochinov et al. (44).Sessions are recorded and transcribed verbatim, then edited to create a narrative or generativity document for patients to bequeath to friends and family. The efficacy of dignity therapy has been evaluated in many clinical and cultural contexts (32–36), often through the use of the Patient Dignity Inventory (37), a 25-item self-report measure assessing domains of symptom distress, existential distress, dependency, peace of mind, and social support. This tool has been validated in several languages (e.g., Greek, Mandarin, Spanish, Italian, German) and among patients with various illnesses, including specific cancers, noncancer terminal illness, and psychiatric illness (38–42). Additionally, a briefer measure called the Dignity Impact Scale has been validated for use as a clinical marker of dignity that can be used pre- and postintervention (43).

More than 85% of patients and families have found dignity therapy helpful and have been satisfied with the intervention (44). In the first randomized controlled trial of dignity therapy compared with supportive psychotherapy and standard palliative care (31), those receiving dignity therapy were more likely to report that the intervention was helpful, enhanced their sense of dignity, changed how their family saw them, and that they felt it would be helpful to their families. Because baseline levels of distress were low in the trial, significant differences on symptom distress, depression, anxiety, desire for death, and suicidality did not emerge. However, trials of dignity therapy among patients with higher baseline levels of distress have demonstrated significant improvements in depression and anxiety symptoms at the end of life (45, 46). Recent systematic reviews of dignity therapy (47, 48) show that it is efficacious for increasing a sense of dignity. Pooled effect sizes on anxiety and depression symptoms have been nonsignificant but have favored dignity therapy over control interventions, and there is evidence that dignity therapy also has enhanced self-reported quality of life. However, heterogeneity in how quality of life has been assessed across studies makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions regarding dignity therapy’s efficacy in this area. It has been suggested that dignity or dignity-related distress should be the primary outcome assessed in examining the efficacy of dignity therapy (43). Other studies have focused on outcomes tracking end-of-life experience, such as increased levels of positive affect, sense of life closure, gratitude, hope, life satisfaction, resilience, and self-efficacy (49).

As research on dignity therapy has progressed, the therapy has been adapted and paired with other interventions, including the life plan intervention (50), family life review (36, 51, 52), and a legacy-building web portal (53). In addition to palliative care contexts, dignity therapy has been used to successfully reduce dignity-related distress in chronic illness (51), bone-marrow transplant (54), major depressive disorder (55, 56), alcohol use disorder (57), health-related trauma (58), and suicidality in incarcerated populations (59).

Meaning-centered psychotherapy (MCP) is an intervention specifically targeting a sense of meaning to mitigate existential distress at the end of life. This intervention has been studied extensively in both individual and group contexts. MCP is a seven-to-eight-session manualized psychotherapy focused on developing or increasing a sense of meaning among patients with cancer. Sessions focus on understanding sources of meaning, identity, legacy, coping with limitations, creativity, and connection. Multiple randomized controlled trials (60–63) have shown significant improvements in overall quality of life, sense of meaning, and spiritual well-being in those who participate in MCP compared with control interventions, such as supportive psychotherapy or usual care.

Emerging evidence supports acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) as an efficacious intervention for patients with a terminal illness, particularly for the understudied and difficult-to-target symptom of anticipatory grief. In ACT, psychological distress is thought to arise from an unwillingness to engage with unpleasant thoughts, sensations, feelings, and memories (i.e., experiential avoidance). The energy required for the aforementioned avoidance prevents or limits the pursuit of valued and meaningful activities. ACT (64) is thus a present-focused therapy that targets increased psychological flexibility through acceptance of situations over which one has little or no control. In palliative populations, acceptance is negatively associated with psychological distress (65). In a cohort of palliative care inpatients, acceptance was the strongest predictor of anticipatory grief, with higher acceptance associated with lower anticipatory grief, above and beyond the effects of anxiety and depression (6). Evidence from a study of patients with cancer (66) also suggests that increased acceptance gained through ACT treatment is associated with reduced psychological distress and improved mood and quality of life. ACT also has a strong evidence base for pain management with efficacy shown among patients with cancer and chronic disease (67, 68); however, research specific to the end of life is limited.

In addition to the aforementioned approaches, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has a solid evidence base for use among patients receiving palliative care and may be particularly helpful in managing common symptoms of depression and anxiety in addition to physical discomfort. Cognitive restructuring related to specific maladaptive anxious or depressive thoughts and behavioral management of physical (e.g., pain and dyspnea) and psychological symptoms can be helpful. Diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and clinical hypnosis can all be useful to aid in coping, self-management, and management of pain (69). These approaches can be adapted as needed for individual patients’ physical and cognitive constraints (70).

Use of one therapy over another, as always, requires consideration of both the presenting concern or concerns of the patient and the skill set and orientation of the therapist. Because no research has directly compared the aforementioned approaches to each other, clinicians engaging in therapy with terminally ill populations are advised to work within an empirically supported framework in which they have received adequate training.

The end of life provides opportunity for rich and meaningful therapeutic work. Clinicians working with patients in these settings have several evidence-based interventions at their disposal, including MCT, ACT, CBT, and dignity therapy. Future research may examine the efficacy, suitability, and feasibility of one modality over the other within palliative care contexts. Although the current article focuses on treatment of the individual, we acknowledge that quality palliative care includes family members in the unit of care. Several interventions focus on dyadic or family therapy, which clinicians with competencies in these areas may find useful for patients in end-of-life settings (71–73). As dignity therapy has gained traction as a feasible and effective intervention in palliative care, it has increasingly been adapted for other populations experiencing significant psychosocial, spiritual, and/or physical distress. Ongoing adaptations of dignity therapy, as well as the provision of dignity therapy across cultures and illness groups should continue to be evaluated. Tools such as the Dignity Impact Scale and the Patient Dignity Inventory will be valuable in assessing outcomes. Similarly, use of telemedicine or web-based interfaces has potential to expand accessibility of this intervention for patients approaching the end of life.